Playing our roles

The history and preservation of Asian board games

Asia is home to a variety of ancient board games, all played with unique pieces that operate under a fixed set of rules. Unfortunately, many of these games are unfamiliar to other parts of the world.

When you think of board games, what do you picture in your head?

Some of us might recall a man in a black top hat, the famous face of Monopoly. Others might think of games like Scrabble or Cluedo. But less likely are we to think of games like Wei Qi or Len Choa.

Indeed, the world’s most popular board games are of Western origin. In a list of the top 400 board games around the world compiled by BoardGameGeek, 92.6% were designed by white men.

This prominence of western actors is also obvious when we observe the boxes of popular board games. Among the top 200 games featuring people on their covers, 82.5% had white-presenting people.

You may think, “It's just a game! Does it matter?”

Our answer is yes, because board games are more than just games to many communities around the world, and particularly in Asia.

They serve as a medium for cultural transmission and help to preserve traditional customs and knowledge for centuries. Our ancestors hid ancient wisdom and philosophy in board games that extended beyond mere entertainment.

For instance, the game Go or Wei Qi, which originated in China 4,000 years ago and is one of the oldest board games in the world, is a strategic game that emphasizes balance, patience, and the art of subtlety. While the rules are simple, the game can be complex, with two players vying to control the most territory on a grid of intersecting lines. It is still popular in China, South Korea, and Japan.

In ancient China, civil servants had to prove their mastery of Wei Qi to prove their worthiness as a leader and qualify for service in bureaucracy. According to a Chinese myth, Emperor Yao (2300 BC–2201 BC) used this game to discipline his unruly playboy son, Danzhu, and get him to change his ways.

Go is just one of many ancient Asian games. These games all serve different social functions while reflecting certain aspects of social life in history. Broadly, these games were played in three main ways: Race, Battle, and Hunt.

Race games

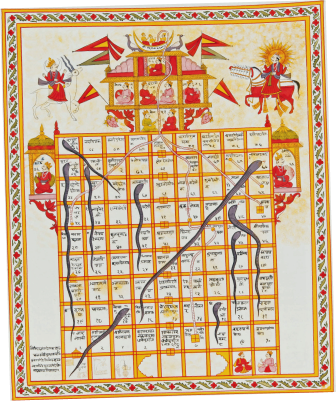

The objective of race games was to be the first to reach the finish line. An example of these would be Moksha Patam, the ancient Indian game that was the main inspiration for the famous Snakes and Ladders game we now know today.

In Moksha Patam, players roll the dice on a board of numbered squares. These squares traditionally represent the layers of understanding in dharmic beliefs. Depending on the players’ rolls, they can climb from the lowest rungs of the ladder all the way to the top of the board, reflecting the role fate plays in one’s life.

This game was regularly used by priests to meditate and pass down moral wisdom to others, acting as an alternative method to sermons.

Battle/war games

In battle or war games, the main goal is to destroy an opponent while protecting one’s own camp. Salpakan, also known as “Game of the Generals”, is a Filipino game that tests the wits of its players. This game hides the identities of opposing pieces, to simulate hidden or unknown information about the enemy, which is common during actual wars.

Beneath the surface of this game lies its actual function as a tool for war education. The gameplay therefore often reminds people of the irregular warfare strategies employed by the Filipinos, which was necessary due to their small and under-resourced armies during wartime.

Hunt games

Hunt games are all about capturing opponent pieces and evading capture as the player does so. An example would be Len Choa, Thailand’s version of the classic game of hunter versus prey.

In this game, “tigers” and “leopards” compete against each other. The “tigers” try to catch as many opponents as they can, by jumping over their pieces. The “leopards” aim to block them, by limiting the number of moves the “tigers” have.

Hunting was important for livelihoods in 19th century Siam, which was why Len Choa became very popular among the community at that time.

Although the board games industry is dominated by the West these days, Asian board game creators and enthusiasts continue to innovate and encourage more people to participate and play.

For example, Origame, a Singaporean board games company, recently released one about Singaporean “table-claiming” culture called “Chope!”. In the game, players must “chope”, or reserve, tables before their opponents.

To promote Asian board games, publishers like Origame also host annual board game festivals where participants try out new games and meet like-minded people. Board game enthusiasts also regularly meet up for friendly games, tournaments, and even brainstorming sessions for new game ideas.

Keeping the board games industry alive is serious business, as they are another method of preserving and passing down unique and diverse Asian cultures. Good news is, we can have fun while doing it!

This story was first published on Kontinentalist’s Instagram on December 12, 2022. The original version was written by Angel Martinez and Adhithi Muruganandam, and illustrated by Griselda Gabriele.

Our team referenced a comprehensive dataset from Cyningstan about traditional Asian board games. Other information was obtained from secondary online sources, with all of them listed below the data visualisations and in the references list.

Ching, Julia, and R.W.L. Guisso, eds. Sages and Filial Sons: Mythology and Archaeology in Ancient China. Shatin, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1991. https://books.google.com.sg/books/about/Sages_and_Filial_Sons.html?id=ynfrlFZcUG8C&redir_esc=y.

Cyningstan. “Games of Asia,” 2024. http://www.cyningstan.com/games/514/games-of-asia.

Pobuda, Tanya A. “Why Is Board Gaming so White and Male? I’m Trying to Figure That out.” The Conversation, March 27, 2022. http://theconversation.com/why-is-board-gaming-so-white-and-male-im-trying-to-figure-that-out-179048.

Singapore Weiqi Association. “About Weiqi,” 2013. https://weiqi.org.sg/Home/AboutWeiqi.